In this article, Tim Husband who provides hearing aids and hearing care in Sheffield and across South Yorkshire discusses hearing aids and music. I hope you enjoy it and it clears up some misconceptions:

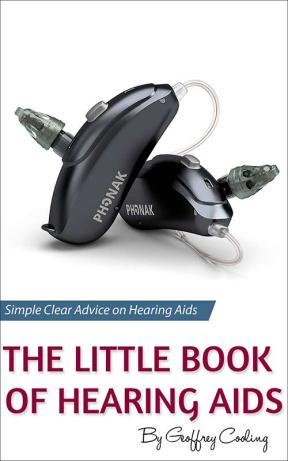

Shortly after the introduction of digital hearing aids manufacturers started to introduce special programs for listening to music into their devices. It seems slightly counter-intuitive to do this. After all if the hearing aids have been programmed correctly this shouldn’t be needed, right? Unfortunately, it just doesn’t work this way. The characteristics of speech are mostly pretty consistent in terms of the volume and pitches involved. Most human speech fits into what is called the LTASS (Long-term average speech spectrum) more informally known as the speech banana:

This shows that the range of frequencies needed to hear speech is quite narrow, between around 200 to 4,000Hz. The actual range of human speech is 80-14,000Hz. As an example the bandwidth of a standard home telephone is only 300 – 3,400Hz and the volume of speech on average is around 65dBHL.

Music, on the other hand, can have tones at the limits of human perception, from 20Hz up to 16,000Hz for the highest harmonic tones. What is called the dynamic range from quiet to loud sounds is also considerably wider. Sounds can range from barely audible at around 20dBHL up to almost intolerably loud at 100dBHL or more. Finally, the performance characteristics of both the amplifiers and receivers (or speakers) in hearing aids are highly tuned for speech reproduction.

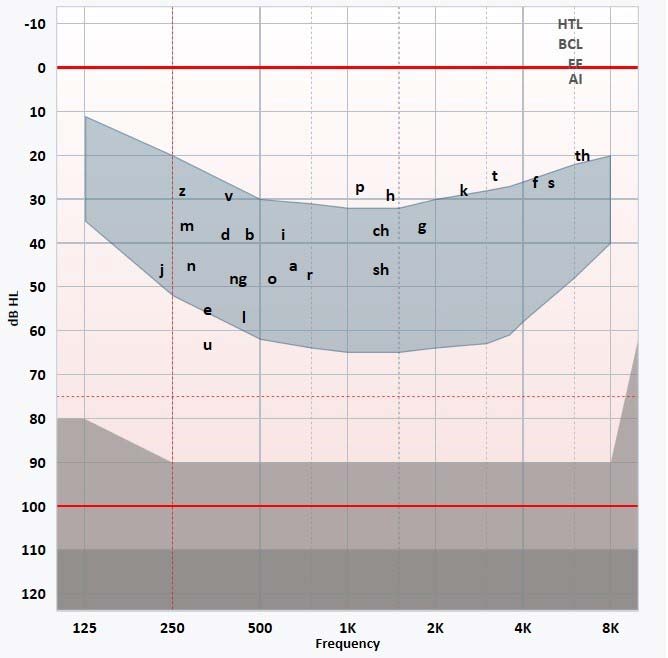

Older hearing aids often have a bandwidth as narrow as 200 – 5,000 Hz with performance dropping off sharply after around 4,500Hz. Some modern commercial hearing aids can offer useful amplification up as high as 9,500 Hz or beyond but the range of volume (more properly called gain) at these high frequencies can be very small. When an amplifier reaches its limit of power it begins to saturate and distort the signal in a process known as ‘clipping’:

When we program modern digital hearing aids for speech we deliberately introduce a range of features to ensure that speech is stable, audible and comfortable. A significant part of this is using adaptive circuits that give what is called ‘wide dynamic range compression’. In short, this is different amounts of volume (gain) for different levels of input sound. A loud sound may require very little gain whereas a whisper might need a large amount to bring the sounds into the audible range for the hearing aid use.

This is all great for speech understanding but this high level of signal processing is the last thing you would want to hear in music. It tends to ‘squash’ the sound so that all of the music sounds to be the same volume, distort the louder sounds through clipping and miss some of the higher pitches out altogether. Digital feedback suppression circuits can also be activated introducing a high-frequency notch or cut out that could, for example, make a piccolo or guitar feedback inaudible.

So what can we do? Some new research conducted in 2019 offers some hope for the music fan with hearing loss. Hearing Aids for Music brought together music psychologists, a Hearing Healthcare Scientist, and a Lecturer in Deaf Education along with a comprehensive advisory body from the world of auditory science and clinical practice. Funded through a grant from the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council this study aimed to examine the listening habits and tactics of Deaf and hard of hearing patients. Over 1,500 people with hearing loss and 100 professionals in auditory science were involved in the study.

The aims of the study were to:

- To explore how music listening experiences are affected by mild, moderate, severe and profound deafness and the use of hearing aid technology.

- To provide evidence of the issues currently affecting hearing aid users with music listening so that technical improvements or advice can be targeted at particular difficulties and listening settings.

- To identify ways in which listeners can optimise their use of hearing aids for perceiving music in everyday listening situations.

- To give hearing aid users with all types and degrees of hearing loss a voice through our work.

Rather shockingly only 15% of those surveyed found listening to music with hearing aids either beneficial or unproblematic. 46% of patients reported having problems ‘more often than not’. It was also noted that very few conversations took place between Audiologists and patients about music. Where discussions did take place it was shown that more time spent addressing this specific aspect did result in improved outcomes when listening to music.

One interesting finding was that patients with milder losses tended to report more benefit from their hearing aids than patients with more severe losses. I would conjecture that this would be a result of both the higher compression ratio’s seen in fittings for severe losses and possible poor aid selection. If a hearing aid has been selected with limited spare power or ‘headroom’ before reaching its saturated or maximum gain state it is far more likely to flatten and clip the wide dynamic ranges of sound found in music. This may point to some fitting strategies to consider when fitting patients for whom music is a high priority.

The study also found a very low uptake of ‘Assistive Listening Devices’ or streaming devices. Hearing Link has an excellent breakdown of the possible benefits of FM or Bluetooth systems here: https://www.hearinglink.org/living/loops-equipment/fm-systems/. Broadly speaking the main benefit for music with these systems is that they cut down on the number of variables that may be affecting the sound quality. For example, the quality of the speakers used, distance from the sound source, room acoustics etc. While the microphones built into the transmitters of these systems tend to be significantly higher quality than can be fitted into a hearing aid they are still not necessarily capable of dealing well with live music. A line out from the mixing desk directly into the transmitter would give significantly better performance.

Finally, Audiologists were asked about strategies they currently employed to enhance the music performance of the hearing aids they fitted. Crucially they reported success when using music during the fitting process. All too often the ‘music program’ is used as a one-click solution but unless you give your patient the opportunity to assess its effectiveness in the clinic it is quite unlikely that it will immediately meet their needs. The website related to the study has some excellent resources both for patients and professionals available at https://musicandhearingaids.org/resources/.

I would offer a few additional points to consider from my own experience:

- If you play an instrument, sing or have a preferred style of music make sure you get the opportunity to listen to it using their ‘bespoke’ music program.

- Giving more control to you. While technically an open fitting is usually better some people prefer the sound of their music when using closed domes. This also helps if the professional has disabled the digital feedback suppression. Ask for two sets of domes for different uses.

- Select your devices carefully. If you want an IIC but have a severe hearing loss you may need to steer towards a more suitable device with sufficient headroom if music is also a priority for you.

- Consider ease of use and efficacy of a manufacturers streaming devices when selecting an aid. People often don’t know whether a streaming device is necessary when they buy an aid but you don’t want to have limited or complicated your choices when you think you do need one.

In summary then, hearing aids can and do work reasonably well for music but additional care and thought needs to be employed to make this happen reliably. With the advent of truly wireless Bluetooth earbuds, Hearables and direct streaming from mobile phones to hearing instruments we are approaching a point where not only are traditional HIFI manufactures considering hearing loss but hopefully hearing aid manufacturers will increasingly consider the importance of the whole auditory experience when developing the next crop of hearing instruments.

If you are into your music, it is worth understanding what Tim has spoken about here and thinking about the tips he has given from his own experience. Remember, ask your prospective hearing care provider do they undertake Real Ear Measurements and if they say no, tell them you will go somewhere else. like us on Facebook by clicking the button below to keep up with our latest posts.